Richard Thompson has played an average of about 100 live shows a year since he was 17. “That’s a lot of notes,” jokes the singer-songwriter, who just turned 72. But for the last 12 months, since the pandemic grounded the live-music business, one of the greatest guitar players and songwriters alive had to find something else to do with his hands.

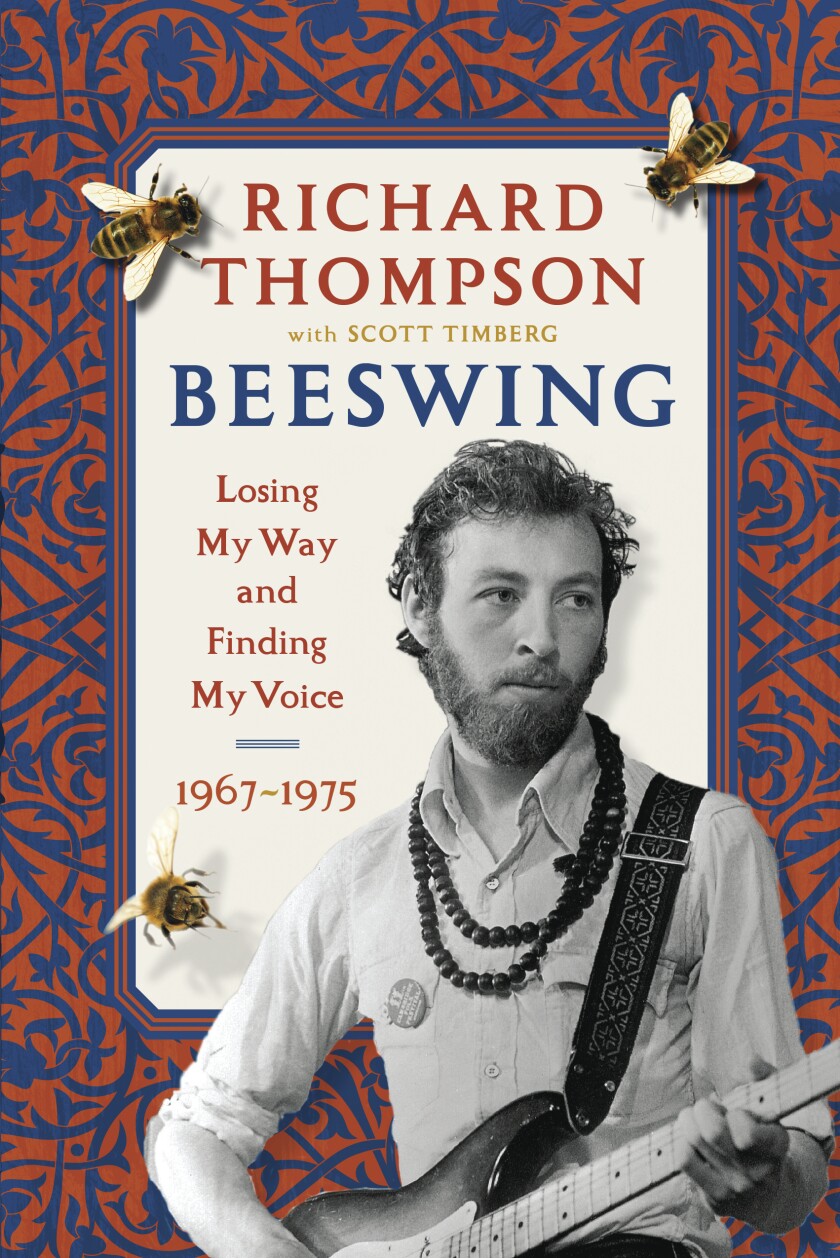

He wrote a book. The new “Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975” is a memoir covering eight years in Thompson’s life, from the beginning of his career in 1967 through his co-founding of the landmark British folk-rock band Fairport Convention and on to his acclaimed recordings with his wife, Linda, and his embrace of Sufism.

The memoir began before the pandemic. With his writer friend Scott Timberg, Thompson made a lot of notes, had a great many conversations and eventually put together a book that is several things: a bay window on rock ’n’ roll’s 1960s breakthrough; the story of how a band crawls forward; and, best of all, a deft and taut description of the creative process, of how a song, or a group sound, emerges.

L.A. Times Festival of Books Preview

Richard Thompson

Thompson will appear at the festival on April 19 to discuss his memoir, “Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975,” with RJ Smith.

$5-$36; RSVP at events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks

Thompson went on from those early years to transform the sound he made. He’s released 18 solo albums that have drawn from British music hall traditions, Sufi philosophy (Thompson became a Muslim at age 23), polkas, rock ’n’ roll and more. He’s been covered by R.E.M. and Robert Plant, and Bob Dylan has sung his “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” Thompson’s celebrated song about a fast motorcycle.

On the phone from his Montclair, N.J., home, Thompson says he was surprised to find that writing a book is more or less as easy as writing a song.

“I think so. The process becomes a bit more disciplined, I suppose. If you write a song you can do it, sometimes, in a matter of minutes. You can’t write ‘War and Peace’ in minutes. The prose process is much longer, but I really enjoyed doing it — I wanted to prove to myself that I could.”

This isn’t “War and Peace” or a folk-rock version of Keith Richards’ doorstop “Life.” Focusing on a handful of years that track Thompson learning guitar, all but sparking a movement to turn rock ’n’ roll from the likes of what the Beatles and Richards’ band were doing and toward a British roots sound, it’s modest and process-oriented and full of good stories.

“Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice 1967-1975.” Algonquin: 304 pages, $28

(Algonquin Books)

In “Beeswing,” the prose is smart and smartly moving, not lingering long on any one thing; in a few words, Thompson is able to tell you a great deal about the origins of his droning guitar sound or the time he sneaked a peek into Joni Mitchell’s notebook while she was on stage playing a show in 1968. Rather than stop forward motion by giving a long description of the band’s transformative singer Sandy Denny, he drops details into the flow — that producer Joe Boyd thought she’d be the perfect voice for Fairport but resisted telling them about her “because he thought she might stomp all over us.” The fierce, ethereal singer auditioned for the band, and then when she passed, she said, “OK, now I want to hear what you do.” She was auditioning the band, and good thing everybody passed.

“One big difference is if you write a book you have editors,” Thompson says. “That came as kind of a big shock to me. As a songwriter you can get away with murder; you don’t have to explain things to anybody. If I write something obscure, people just think I’m a tortured genius. But in this kind of writing, somebody will actually say, ‘What did you mean with that?’”

Back in the 2010s, the book was born in the mind of a huge Richard Thompson fan. Timberg was that and a lot of other things: an arts journalist for the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere capable of writing about both John Ashbery and PJ Harvey; author of a book on the struggles to make a living in the arts; a musician, husband and father. He wanted to read a book by Thompson on his early years and, ultimately, reached out to Thompson, and then reached out some more, checking in regularly for a few years until they agreed on how a project might proceed.

Those who knew Timberg in 2019 might have heard him talking about finishing up the Thompson book he’d conceived, or his ideas for future projects. None of which happened. In December 2019, before “Beeswing” was completed, Timberg died by suicide. He was 50.

“I heard about Scott’s death from our mutual literary agent. I shared condolences with his family and some of his colleagues from the L.A. Times,” Thompson says. “It was devastating news, especially because of the lack of any indication that this was about to happen. A few people thought there was some history there, but I was unaware of it. It derailed me, and the book project, for a while. We lost a good man.”

“Richard’s music was always sort of a presence, in the background,” says Timberg’s wife, writer and librarian Sara Scribner. “One thing that really appealed to Scott is, he didn’t feel that Thompson got his due. To Scott he was as good as Dylan, as good as Leonard Cohen, and he couldn’t figure why he wasn’t getting the recognition.”

“I put him off for a couple of years,” says Thompson, and then they started meeting regularly, Timberg asking questions and recording the musician’s answers. “He would interview me, and I’d ramble on about stuff.”

In 2018, Thompson moved to Montclair after living in Pacific Palisades for some 30 years. Ultimately, Thompson took on the task of writing the draft himself and sending it to Timberg for revising.

Timberg, an unabashed Anglophile who had lived in Sussex for a year, admired Thompson’s dark vision and his love of history — to both of them, the past, even the ancient past, had a way of reaching up and laying a finger on one’s daily life.

Scribner says she has been going through her late husband’s files, putting together a collection of his work that will eventually be published. She came across a piece she didn’t know he’d written about Thompson in the 1980s, before they’d met. “It’s hard to explain, when somebody you love dies the way Scott did, it complicates everything,” she says.

“It just gives me a lot of pleasure to see that the book is coming out and that it’s got his name on it. It kind of revives him in my mind a little bit.”

In “Beeswing,” Thompson tells a story about Fairport Convention headlining a 1970 show that also featured glam proto-punk band Mott the Hoople. The crowd loved the openers, then turned on Thompson and company, their fiddle tunes and songs of sea dogs and magic. They were booed throughout, and the rhythm guitar player threatened to fight the whole crowd.

Thompson and the band quickly considered going forward the Mott way: “Rubbing the guitar necks together, doing synchronized steps, shaking our long hair in feigned ecstasy.” They tried it all at their next show, even motorcycle boots, and it worked — “it went down an absolute storm”; the crowd cheered them ceaselessly. Was this what they wanted to be? They decided not, and never did it again.

“Beeswing” documents how musicians pick up influences but also, crucially, how they curate, edit themselves and trim back all the things that don’t quite fit.

“Most English bands of the time chose to be influenced by blues and American rock ’n’ roll,” Thompson explains. “We were too, but then we came up with the idea of listening more to where we came from.”

His book documents a beloved band’s prime existence: “We rattled a few windows, without actually blowing the house down.” It describes his musical life with wife Linda Thompson (together they recorded “Shoot Out the Lights” in 1982, still considered among his finest moments), and then his launch as a solo performer. That’s where the book winds up — a quick endpoint that doesn’t feel like a finish.

An author photo of Richard Thompson.

(David Kaptein)

Because it’s not. He describes in “Beeswing” the early days of terrible guest houses where “all bedding appeared to be damp nylon” and dinner was a lettuce sandwich. Now, with coronavirus restrictions lifting, Thompson says he can’t wait to get back out.

“Bookings are coming back,” he says eagerly. He looks forward to the life of the road, though now it involves a bus instead of a van, and something better than lettuce between the slices of bread.

“The life is a lot easier now. And we stay in better hotels too.”