To make his sultry and exploratory new album, “Gold-Diggers Sound,” Leon Bridges started working nights.

The Grammy-winning soul singer known for his exacting throwback flair used to keep regular 9-to-5(-ish) hours in the recording studio. But after collaborating for a few years, Bridges’ producer Ricky Reed wanted to shake things up by moving their sessions to after dark.

“I was reluctant at first because I like to go out late and have a good time,” Bridges recalls. “When you look at how rappers do it, these guys are going in at midnight. I’m like, I don’t know how y’all motherf—ers do that.” He laughs. “I got to be there for last call.”

The solution: combining the bar and the studio into one.

As its title advertises, Bridges, 32, laid down his third LP at Hollywood’s Gold-Diggers, a storied multiuse venue on Santa Monica Boulevard that houses a refurbished dive bar, a studio complex and a boutique hotel behind a grimy-looking facade. In the 1980s, the place hosted exotic dancers while hair-metal bands rehearsed in the back; before that, B-movie king Ed Wood used the space as a soundstage.

For Bridges, Gold-Diggers promised a kind of total vibe immersion. Instead of recording till dinner, the singer from Fort Worth (who slept in a room upstairs) got going every day around dusk; instead of partying elsewhere afterward, Bridges kept the drinks coming from down the hall. In search of further atmosphere, he opened the door to old friends from home and new pals in Los Angeles, including the saxophonist Terrace Martin and twin sisters Paris and Amber Strother of the R&B group King.

Says Reed, who co-produced the album with Nate Mercereau and has also overseen records by Lizzo and Kesha: “I’d heard about Leon’s wild nights on the town. So I thought, What would it be like to have that guy in the studio? Maybe it would unlock something.”

Indeed it did. With “Gold-Diggers Sound,” Bridges leaves behind the mannered late-’50s/early-’60s revivalism of his early music, which garnered countless comparisons to Sam Cooke, in favor of a more modern, freewheeling approach. The songs blend bleary synths and jazzy horns over throbbing programmed grooves; the lyrics, which Bridges delivers in a silky voice with just the right amount of grit, ponder desire, faith, depression, family and — in “Sweeter,” originally released last year in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by police — the vexing persistence of American racism.

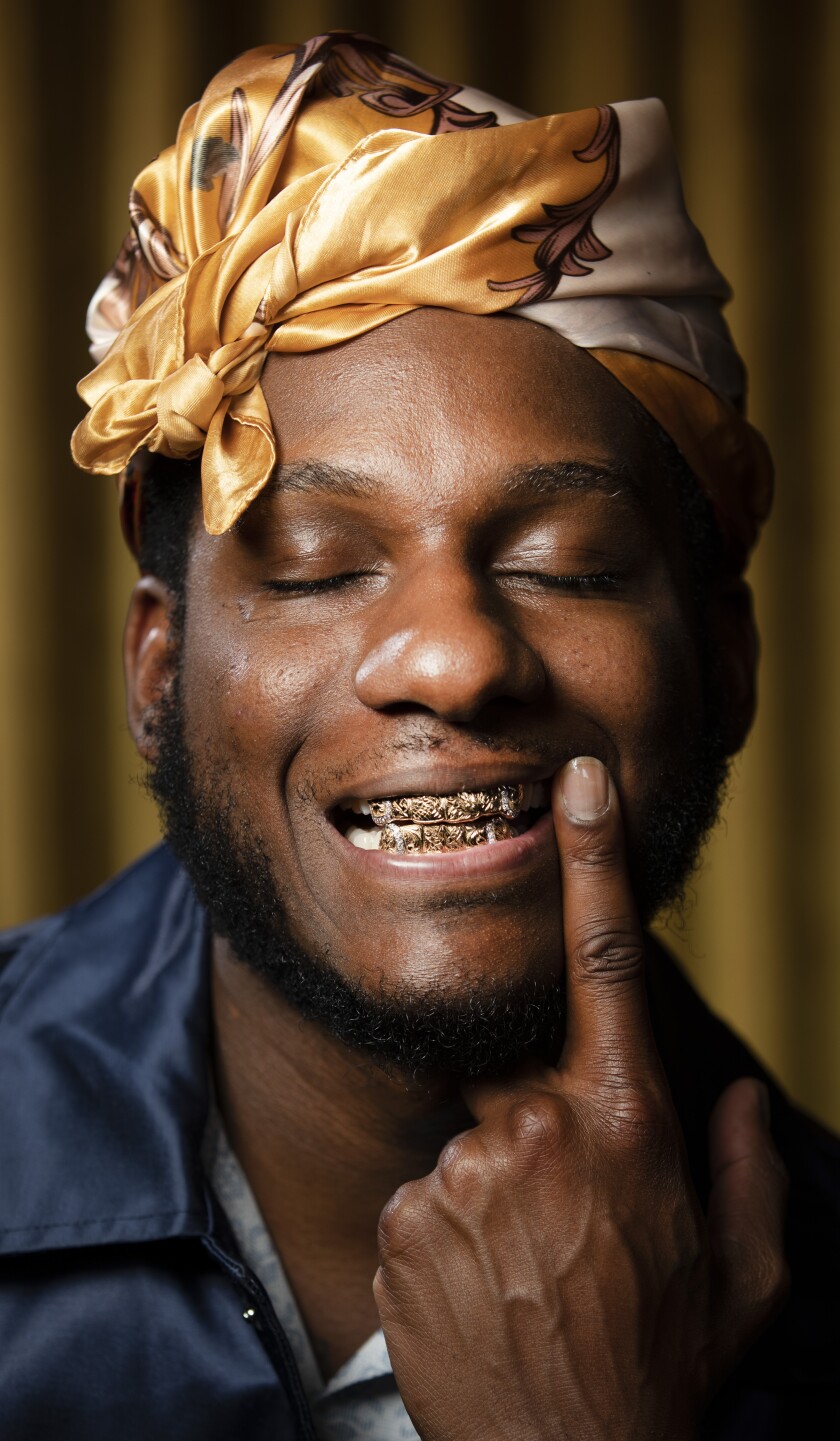

The result, Bridges notes with pride, unsettles the idea of “a retro artist living a retro life” that coalesced around him with his 2015 debut, “Coming Home,” and its 2018 followup, “Good Thing.” Back then he took up Cooke’s crisply romantic style because he wanted to “carry the baton” for a sound that had fallen out of popular favor, he explains on a recent afternoon at Gold-Diggers, which began its current incarnation three years ago under L.A. nightlife impresario Dave Neupert. Lounging in an alley between the bar and the studio, Bridges wears a satiny track jacket, his hair beneath a gold scarf and his teeth behind a gold grill — a marked contrast with the sharply tailored suits he favored on the road behind “Coming Home.”

Leon Bridges outside Hollywood’s Gold-Diggers.

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

His debut, and its precise historical imagery, led to high-profile soundtrack placements and to a gig performing for the Obamas at the White House. But it also boxed him in to a perception that felt untrue to Bridges’ real life — for starters, that he was uninterested in (or even dismissive of) hip-hop, when in fact “I’m probably one of the biggest Young Thug fans out there,” he says.

With his new album, Bridges says, “I finally shaped a sound that feels like me,” though he knows the shift may trigger suspicions among fans of his more old-fashioned stuff.

“People want to put boundaries on Black self-expression,” he says. “When I do anything that deviates from what I’ve done, it’s deemed disingenuous or that I sold out — ‘Oh, the fame changed him.’” In conversation, Bridges chooses his words carefully, even as his fingers tap out a jittery rhythm on his leg. “I have a grill in my mouth — that’s Black culture. If I’m listening to hip-hop, that’s still Black culture. Rocking with some James Brown — Black culture.

“You guys don’t even know. I’ve been doing this s—.”

Looking back, does he regret starting out in a style that made him easy to pigeonhole?

“Not at all,” he replies, “because if I stepped out with something different, I don’t think I would’ve been as successful. With ‘Coming Home,’ it was a familiar sound that people could immediately attach themselves to. But reinventing yourself is what Marvin Gaye did. It’s what Sam Cooke would’ve done.”

Bridges grew up a shy, quiet kid in Fort Worth confused about where he fit in. He remembers digging the “antiquated aesthetic” of Harry Connick Jr.’s “A Wink and a Smile,” from the “Sleepless in Seattle” soundtrack that his mother played obsessively in the car. And he got a sense at a young age that he could sing when his father responded enthusiastically to Bridges’ busting out “Hakuna Matata,” from “The Lion King.”

With his new album, Leon Bridges says, “I finally shaped a sound that feels like me.”

(Myung J. Chun/Los Angeles Times)

He didn’t perform in front of people, though, until his senior year of high school when he danced to Mims’ 2007 rap hit “This Is Why I’m Hot” at a talent show. “At the time no one knew that I could dance,” he says. “It was like … boom.” Yet the “minuscule bit of fame” he earned soon receded; after losing his virginity to a prostitute, he became a born-again Christian and stopped listening to secular music for several years.

Today he’s in a “weird limbo” with his spirituality. He knows that his lifestyle — “drinking, cursing, fornication,” as he puts it — is out of alignment with the “very legalistic Christianity” he came up in. “So a part of me is like, ‘What if I die and I go to hell?’ Then the other part of me is like, ‘Maybe it’s not true.’”

Bridges’ experience with religion is what drove him to write “River,” a barebones hymn from “Coming Home” that’s been streamed more than 250 million times on Spotify and YouTube. “That usually doesn’t happen with music of that nature,” he says, and though he means a song about “surrendering to the good Lord,” the same applies for one that consists of nothing more than voice, guitar and tambourine.

For “Gold-Diggers Sound” he knew he wanted to use a broader palette; half the record, he reckons, was written from scratch at Gold-Diggers as he and his musicians — among the other players are keyboardist Robert Glasper and trumpeter Keyon Harrold — found their way together toward the songs.

“Leon would sing improvised melodies in real time, and at the end of the night, pretty intoxicated, we’d listen back and say, ‘OK, this one’s dope,’” says Reed, who fondly recalls burning through Bridges’ stash of drink tokens. “Then we’d chop up an arrangement on the spot and come in the next day and cut vocals.” (The album’s other half began with songs Bridges co-wrote with pop pros including Justin Tranter and Dan Wilson.)

Bridges hopes “Gold-Diggers Sound” similarly expands his audience. “My circle has always been Black, but initially the demographic at my shows was predominately white,” he says. “I’d look out and be like, ‘Damn, where are my people?’ I’ve been criticized for it too: ‘I went to his show and them white people were loving it.’” Yet with its moody introspection and its unvarnished edges, the new LP seems less likely to fulfill anyone’s genteel fantasy of a bygone soul-music tradition.

He’ll find out who connects with the music when he heads out on tour this fall, including stops at the Bonnaroo and Governors Ball festivals and an Oct. 11 show at L.A.’s Wiltern. Bridges is excited to get back onstage after COVID, though he wonders how long the road life is for him. During the pandemic he bought “a little plot of land” in Fort Worth where he plans to build a home for the wife and kids he’s pretty sure he sees in his future.

“Do I really want to be running around at 40, 50 years old?” he asks, time on his mind as always. “Shoot, that’s right around the corner.”