For the past few years, the Armenian American musician Arshag Chookoorian has been working through memorabilia stored in his family’s garage that tell a remarkable story of an unsung entertainer’s life in show business.

With the help of his friend Harout Arakelian, a Tujunga-based music collector dedicated to preserving the earliest Armenian American recordings, Arshag has been documenting the legacy of his late father, the beloved Los Angeles comedic singer, actor, oud player and bandleader Gaidzog “Guy” Chookoorian.

Guy died on Jan. 31 at 97, of natural causes. His passing marks the end of an era. The evidence is gathered in the records, scrapbooks and press clippings stored in the single-story Northridge ranch home that Arshag, 65, shares with his wife and two teenage sons.

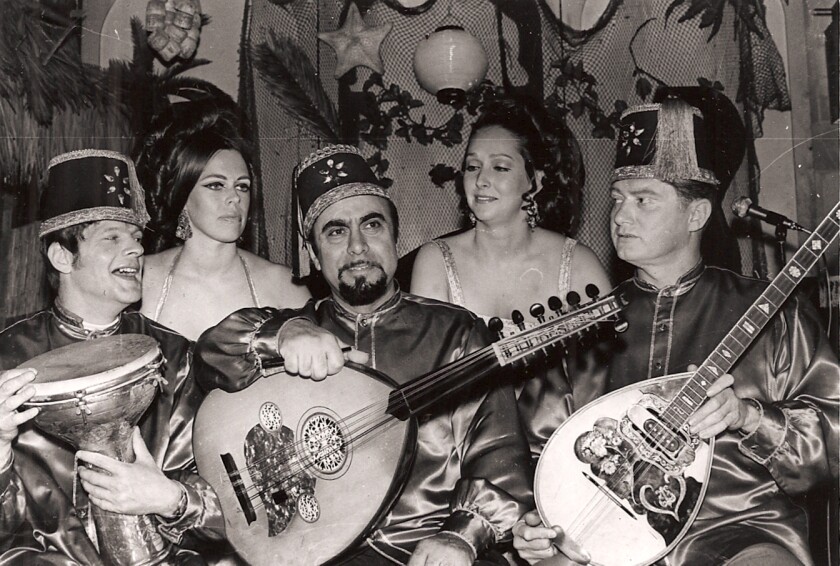

Guy Chookoorian, center, with his band and troupe of belly dancers. Starting in the 1960s, they toured as a Middle Eastern musical revue.

(Arshag Chookoorian)

When his father’s singular musical style first caught the attention of fellow Armenians in Los Angeles, Arshag says, crowds were thrilled. “They thought it was the greatest thing in the world because until then [no] one had ever done anything like that. My dad was the originator.”

Starting in the 1940s, Guy released singles on his own Lightning Records as Guy Chookoorian and His Amoti Four, the “In” Sultans and the Guy Chookoorian Orchestra. Wildly charismatic and often comedically inclined, the songs now offer revelatory information on dialects and endangered folk melodies. A number were Armenian adaptations of contemporary American hits, which he sold at picnics, dances and weddings.

Chookorian took advantage of the tiki and belly dance crazes of the 1950s and ’60s through revues that toured America and Canada. He acted too, landing bit parts in TV series including “Full House,” “Charlie’s Angels” and “General Hospital.” In less racially representative times, his “exotic” look landed him jobs portraying a United Nations’ worth of ethnicities. Press photos show him posing as an effete Frenchman, a sombrero-wearing Mexican, a white sailor and a turban-wearing Arab.

Among the oldest surviving first-generation Armenian American musicians to make a living in Hollywood — or at least as a character in its mise en scéne — his death concludes a chapter extending back more than a century.

“He was a staple of the L.A. music community when it came to Middle Eastern music or music from that region,” says Arakelian, 45. Guy was best known for his comedic records, “but when you look at his body of work, it’s more than that.”

It’s a symbol of not just a life well-lived but of the way in which Armenian identity has both flourished and assimilated into the so-called American ideal. In Southern California that identity remains a powerful force.

Approximately 200,000 residents of Armenian descent live in Los Angeles County. Across the past hundred years, ethnic Armenians in search of a better future have flocked to the West Coast. Starting amid World War I, the U.S. government began easing restrictions on immigrants from the Middle East, and communities formed in Fresno and Los Angeles. Between 1980 and 1990, the number of Armenians in L.A. County more than doubled, to 115,000.

“In the ’80s, our dance band was working every Armenian function in town, and we had sometimes two or three gigs per weekend — weddings, banquets, dances,” says Arshag, who, along with his sister Araxie, performed alongside his father for decades.

Some of this story resides in Arshag’s home, held on records and albums that Guy released on Lightning. Each is more singular than the next. Armenian-language versions of midcentury novelty hits that tickled the ears of American teens: “Open the Door, Richard” (“Tooré Pats, Dikran”), “Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette” (“Dzukhé, Dzukhé, Dzukhé”), “The Ballad of Davy Crockett” (“Davit Amoo”), “Come on-a My House” (“Yegoor Eem Doonus”) and dozens of others.

But Chookoorian was more than an entertainment asterisk.

“Guy Chookoorian and the generations he played for were survivors or the children of survivors of the genocide,” says Salpi Ghazarian, director of the USC Institute of Armenian Studies. They carried heavy burdens, including traumatic memories, she adds, “but they were also ambitious [in] wanting to survive and thrive. And music, food and church were the paths to thriving. Guy Chookoorian gave them a light way of being Armenian, a mirror to their own homes and families, in humor, with warmth.”

Among those charmed and delighted by Chookoorian was an Armenian American family whose fame would one day eclipse that of any American family. The late Robert Kardashian, a prominent lawyer who represented O.J. Simpson during his murder trial, was a first-generation Armenian whose family moved to the United States in 1917. Well before Kim, Kris and Kourtney became reality TV stars, the Guy Chookoorian Orchestra played parties at the Kardashian compound.

Arshag and Araxie played that gig. “They had us set up on their tennis court,” Arshag recalls. Though he can’t remember if it was before or after the Simpson trial, he knows that by then “the Kardashians were the Kardashians.”

Arshag still has his dad’s old instruments — the ouds, bouzoukis, banjos, synths and mandolins. He’s saved a few fancy outfits and fezzes that Guy used to wear during solo and band jobs at restaurants such as Haji Baba’s in Inglewood and Arabian Nights in Fresno. He also holds treasured memories of supporting his dad during his later years.

“We’d dress him up and get him into the van and do our gigs,” recalls Arshag. “He did all the schmoozing, and my sister and I would do the sweating. But we didn’t care. He was actually able to perform for a lot longer because of that.”

Guy Chookoorian and his oud.

(Arshag Chookoorian)

Guy’s life began in Kenosha, Wisc., a few years after his father and mother, Roupen and Srpouhi Chookoorian, had settled after enduring the horrors of the Armenian genocide. The ethnic cleansing by Turks led to mass killings of what historians estimate was up to 1.5 million Armenians amid the upheaval of World War I.

A landlocked country in Western Asia bordered by Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Iran, the mountainous region has long been home to ethnic Armenians. During the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Turkish forces intent on controlling its eastern border embarked on a murderous campaign to ethnically cleanse the region. Armenians fought back.

Roupen was a member of the Armenian resistance but had been forced to flee his family and the country. While Srpouhi was still in the Eastern Turkey Province of Yerzinga, Arshag says that Turkish fighters, as part of a coordinated massacre of men and male children, “forced her to throw her baby in the Euphrates River.”

Guy’s mother channeled her grief into action. After the Russian army arrived, she devoted her time to helping track Turkish war criminals and Armenian orphans. Working as a silk trader, she gained the confidence of those with information. She reportedly helped free hundreds before ending up in a refugee camp in the Black Sea port city of Poti, Georgia, where she spent the next eight years.

When Roupen was informed of her whereabouts, he returned to Armenia to find her. Guy wrote a song about the harrowing event. Called “Mission to Poti,” the instrumental captures the drama of the moment. In liner notes to a collection of his music, Guy sets the scene: “Picture if you will my father and a hired driver in a horse-drawn carriage on a dark night rushing along a mountain road through a driving rain with the sounds of cannons and guns in the distance.”

They immigrated to America in 1922 and gave birth to Gaidzog (Guy) and his sister Dziadzan not long after. One possible sign of their hopes in America can be found in the names of the two children. “Gaidzog means ‘lightning,’” Arakelian notes, “and Dziadzan means ‘rainbow.’ Like, ‘We made it through the darkness and now we have an opportunity for a brighter tomorrow.’”

The family moved west to Fresno while their children were in elementary school. A writer, musician and cobbler by trade, Roupen opened a shoe store for the growing community of uprooted Armenians.

Guy went a different route, at least at first. Focusing on new world tunes, he got his start as a teenage cowboy singer in the late 1930s. He and a friend landed a 15-minute gig on a Fresno AM radio station that aired during the morning farm report. He graduated from high school and was planning on studying premed when World War II erupted. After serving as a B-17 “Flying Fortress” radio operator-gunner, Chookoorian landed in Hollywood intent on turning his love of comedy and song into a career.

As he did so, he fed his family — wife Louise, son Arshag and daughter Araxie — however he could. Guy worked at a soap factory and a food processing plant. He cleaned pools for nearly a decade. When the belly-dancing craze hit, he got club gigs on the Sunset Strip at Ciro’s (now the Comedy Store). It was a hustle, for sure, but Guy was making progress. Fronting acts including the Guy Chookoorian Orchestra, Moosh Mountaineers and Guy’s Hyes, he played at the many Armenian American picnics and dances across the state.

Guy Chookoorian, left, with actor John Stamos on the set of “Full House.”

(Arshag Chookoorian)

Regardless of the venue, he always made sure he had plenty of Lightning Records to sell at a buck a piece.

The first release, an Armenian-language version of the early rhythm and blues smash “Open the Door, Richard” (itself based on a Black vaudeville routine), came out two years after Chookoorian moved to Hollywood in 1945. Thinking it might be a funny bit, he translated the song into Armenian. In an interview before his death, Guy called the song “a great stunt to do on stage.” He decided to record it. Called “Tooré Pats, Dikran,” the single sold a few thousand copies, which, noted Guy, “was great for the Armenian market at that time.”

“He was always a funny guy,” says Arshag. “He told me that when he was a kid when he went to the library he would only check out books on comedy. He studied humor, so he started doing jokes at Armenian functions.”

On first listen, you might think that Guy was merely singing comedy songs for a lark, “but it was a lot more dynamic than that,” Arakelian says. “They weren’t straight translations or just having fun. He would intentionally add Armenian notes in certain places because there was a change in the story.” “Davit Amoo,” Chookoorian’s adaptation of “The Ballad of Davy Crockett,” is “basically an accurate telling of the Armenian migration to Los Angeles,” explains Arakelian.

Chookoorian followed commercial trends. For the pounding 1957 rock ‘n’ roll single “Armenian Rock” he borrowed a melody that he’d learned from his oud-playing father. Like most of his records, it was recorded at Gold Star Studios, where the Beach Boys created some of “Pet Sounds.” Both it and its A-side, “Opal from Constantinople,” are hidden gems of early California rock ‘n’ roll.

Guy was a serious student of the oud, as well, believed to be the first-ever oud player in the Hollywood musicians’ union. To white travelers dining at a Middle Eastern restaurant near LAX, his solo performances might have seemed little more than mood enhancers produced by an exotically costumed actor playing the part of “Middle Eastern musician.” But his gorgeously contemplative fret work was so much more. He composed his extended piece “Takhsim in E,” he explained in liner notes, while working at Haji Baba’s restaurant. Recorded onto 8-track tape during one night’s performance, a half-century later it still mesmerizes.

“When the music contractors were looking for bizarre music,” says Arshag, “they’d called the union and say, ‘The only guy we know who plays this weird stuff is Guy Chookoorian.’”

Chookoorian never achieved enough acclaim in any one endeavor to become a star, but in him, collector Arakelian saw a figure not only determined to make it as an entertainer but eager to be a translator for the Armenian American community.

What Arakelian refers to as “the genius” in Chookoorian’s work lies in the ways in which he preserved onto wax an endangered history. The lyrics for his Armenian-language adaptations of songs such as “Open the Door, Richard” and “The Ballad of Davy Crockett,” says Arakelian, “would be pretty much verbatim” to the original, “but he would add an introductory monologue.”

At first Arakelian considered these intros quaint. “But one day I woke up, and I was like, ‘Oh my God, how precious is that? We’re hearing this dialect that’s probably going to die off at some point and here it is documented it for us.’”

Armenian-American music collector Harout Arakelian’s goal is “to reintroduce the music to the audience that doesn’t know about it.”

(Jason Armond / Los Angeles Times)

Arakelian’s own pursuit of early Armenian music in California led him to reach out to the Chookoorian clan in 2017. He grew up as a jazz and hip-hop fan but had an overarching curiosity for early Armenian music. Information wasn’t easily accessible so he dug in. The collector’s advocacy has helped advance the legacies of Chookoorian and other Armenian American musicians including composer Alan Hovhaness and oud master Richard Hagopian. By day a video editor who works in the legal community, were it not for Arakelian and others’ work during off-hours, whole swaths of information might be lost.

Whether young Armenian Americans have any interest in digging into the culture created so long ago and far away is another question, but it is in part what drives Arakelian. His mission, he says, is “to reintroduce the music to the audience that doesn’t know about it.”

He’s been doing his best. A few years ago Arakelian gave a presentation on Chookoorian to about 100 people at Abril Bookstore in Glendale, the center of Armenian life in L.A. Though Guy wasn’t well enough to attend, the Chookoorian clan was out in full force. They were thrilled with the reception, Arshag says.

“After decades of his music being out there, you start to take it for granted that nobody even remembers anything, right? Then suddenly there was this new spark in my dad and his career.”